More Action in "PC"

MOVIE SNEAKS | SUMMER 2008

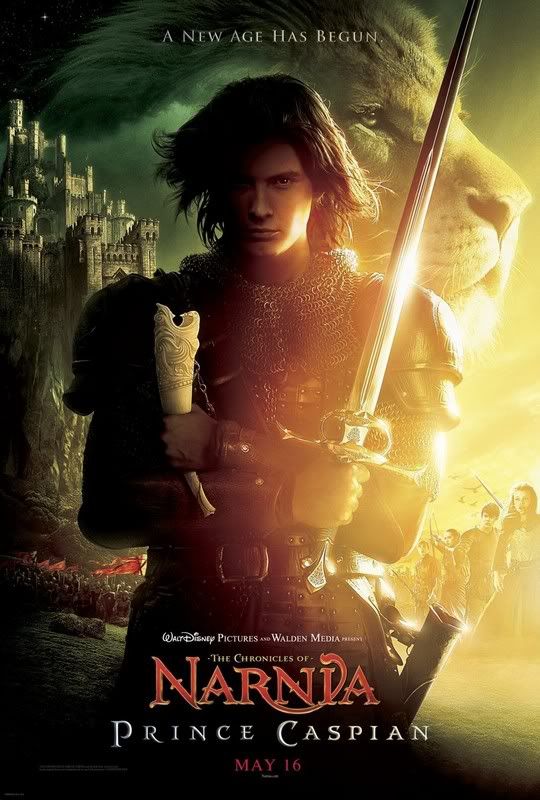

Action speaks louder in 'The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian'

The sequel takes battle scenes and spectacle to higher heights.

By John HornLos Angeles Times Staff Writer

May 4, 2008

London

IT WAS the crowning battle in "The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian," but as the scene played out in a Soho dubbing theater, it wasn't yet crowning enough. Huddling with half a dozen editors in mid-March, director Andrew Adamson was racing to complete the film's sound mix, looking for any opportunity to make "Prince Caspian's" final battle just a bit more powerful. "The Telmarine army is a chatty bunch," the 41-year-old director told the mixing team after reviewing the buildup to an epic clash between the occupying Telmarine troops and the sympathetic Narnians, led by Caspian (Ben Barnes) and Peter Pevensie (William Moseley). "I couldn't really hear the hooves of their horses. So let's make it less chatty, more stomping."

Adamson and screenwriters Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely have labored to bring that precise instruction -- action, not talk -- into every frame of the second film based on C.S. Lewis' seven-part allegorical fantasy series, which opens May 16. It's as much necessity as invention: Audiences, particularly in the summer, demand bells and whistles, and yet there's hardly any overt spectacle (not to mention driving narrative) in Lewis' 1951 book.

Caspian appears just a bit more in the novel than Godot does in Samuel Beckett's famous play, and the concluding battle that fills a good chunk of Adamson's movie is recounted in the space of just a few paragraphs. Yet as "Prince Caspian's" creative team conjured up more conflict and peril, they also had to remember the millions of elementary-school-age moviegoers who flocked to the first film nearly three years ago.

"I think it's a bit darker, and I think it's more complex. It's a much more sophisticated movie," says Mark Johnson, who produced "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" and "Prince Caspian." "There are a lot more liberties that Andrew and Markus and McFeely had to take than they did in 'The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.' "

As the filmmakers ratcheted up "Prince Caspian's" stakes, they had to be mindful of the PG rating they were contractually obligated to deliver to Disney and Walden Media. At one point late in the game, Adamson had to add a few frames to make it clear to the Motion Picture Assn. of America's ratings board that a helmet lolling on the ground didn't really have some unlucky person's head in it.

THE EYES HAVE IT

ADAMSON, WHO also directed the first two "Shrek" films, wasn't sure he wanted to return to Narnia, even though the first film was acclaimed by critics, embraced by families and has grossed more than $748 million worldwide. But he looked into the eyes of the then-10-year-old Georgie Henley and changed his mind.

Henley plays Lucy, the youngest of the four Pevensie children who enter Narnia's timeless world. When Adamson was directing Henley in the first film, she couldn't cry when he needed her to, after the lion Aslan's death. Henley had always wept watching "The Lion King," so Adamson cued its DVD up, but that didn't work, either. Running out of ideas, the director shared with Henley his doubt that he would direct the next film. The tears finally came.

Months later, with the first film completed, Henley sidled up to the New Zealand-born director. "When you said you weren't going to do the sequel, were you saying that just to make me cry or because you really didn't want to do the sequel?" she asked Adamson. "That made me want to do it," the director says. "When you look into those eyes, you can't say no."

If that was an easy enough decision, wrestling Lewis' succinct book into a movie was far more problematic. In Lewis' telling, some 12 months have passed since the four children left Narnia, but it's 1,300 years later in the lands where the White Witch once ruled.

In the intervening centuries, as a dwarf named Trumpkin relates to the children, the Narnians have been driven underground by the usurper Miraz and the Telmarines, descendants of pirates. Caspian, the son of the rightful (but slain by Miraz) King Caspian, has had to flee before he too is killed. With the Telmarines massing for battle, the Narnians need the eldest Pevensie boy, Peter, and Caspian, who have their own rivalry, to somehow save their race.

It sounds more exciting than it reads. Four consecutive chapters are told in flashback, and Caspian vanishes from the story for dozens of pages at a time. While the book may be a classic of children's literature, it doesn't scream movie.

Adamson and his collaborators steered the book's characters toward three concurrent story lines: Caspian's flight and ascension, the children's discoveries and maturation, and Miraz's implicitly genocidal campaign against the Narnians and their rightful king.

At the same time, Adamson says, "I was trying to find the emotional reality" of the movie. If the first "Chronicles of Narnia" was a fable of faith and sacrifice, the second became a parable of loss -- how the passage from childhood to adulthood inevitably means that as you take on something new, you must abandon something else: Innocence is replaced by doubt, trust by suspicion, comfort by insecurity. It's an idea shaped in part by Adamson's experiences in Papau, New Guinea, where he lived as a child. He could never bring himself to revisit it as an adult, he says, "because the place that I grew up in had completely changed and I couldn't confront that loss. . . . But you don't want to create a movie that's a bummer, and our first draft was pretty cynical."

That cynicism has been replaced by mounting (and sometimes made-up) conflict; it's clear from "Prince Caspian's" first frenetic frames the book is more guide than bible. Lewis writes that when Caspian fled Miraz's castle, "All night he rode southward . . .," and that's about as nail-biting as it gets. In Adamson's opening sequence, it's a pounding chase filled with peril. When Trumpkin (Peter Dinklage) later tells the children, "You may find Narnia a more savage place than you remember," he isn't kidding.

"I've really tried to stay true to the major themes of the book, the major events, and also have some invention," Adamson says back in his London postproduction suite, where eight assistant editors are frantically cutting in special effects shots (the first film had nine months in which to finish after photography wrapped, while "Prince Caspian" had about seven). Close readers of the book will notice that one of the movie's biggest departures is how quickly Caspian and Peter join forces.

The scale of the film also is noticeably grander. The opening sequence alone includes footage shot in the Czech Republic, Poland, New Zealand and Slovenia. "I think it's a much more beautiful movie," says Oren Aviv, Disney's production president, "just in terms of the scale and the scope of the locations." Even with unfinished effects, "Prince Caspian" tested better in a research screening than the first film.

SCORING UNDER THE GUN

WITH only a few weeks left to lock the movie, Adamson, in the Soho scoring stage, had asked composer Harry Gregson-Williams to move up a scoring cue by a few frames.

Adamson made the decision around 2 p.m., and by 4 p.m. at Abbey Road Studios (yes, that Abbey Road), Gregson-Williams already had made the change. Nervously chewing at the stubs of his fingernails, the composer in the next few days would assemble a 119-voice choral group. "I still have the whole battle scene to do," he says. If the film has approximately two hours of score, Gregson-Williams still had 30 minutes of music to finish.

Adamson isn't worried, though. The second movie may have been trickier at every turn, but it nevertheless was coming together. In Narnia, magical things happen.

Adamson and screenwriters Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely have labored to bring that precise instruction -- action, not talk -- into every frame of the second film based on C.S. Lewis' seven-part allegorical fantasy series, which opens May 16. It's as much necessity as invention: Audiences, particularly in the summer, demand bells and whistles, and yet there's hardly any overt spectacle (not to mention driving narrative) in Lewis' 1951 book.

Caspian appears just a bit more in the novel than Godot does in Samuel Beckett's famous play, and the concluding battle that fills a good chunk of Adamson's movie is recounted in the space of just a few paragraphs. Yet as "Prince Caspian's" creative team conjured up more conflict and peril, they also had to remember the millions of elementary-school-age moviegoers who flocked to the first film nearly three years ago.

"I think it's a bit darker, and I think it's more complex. It's a much more sophisticated movie," says Mark Johnson, who produced "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" and "Prince Caspian." "There are a lot more liberties that Andrew and Markus and McFeely had to take than they did in 'The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.' "

As the filmmakers ratcheted up "Prince Caspian's" stakes, they had to be mindful of the PG rating they were contractually obligated to deliver to Disney and Walden Media. At one point late in the game, Adamson had to add a few frames to make it clear to the Motion Picture Assn. of America's ratings board that a helmet lolling on the ground didn't really have some unlucky person's head in it.

THE EYES HAVE IT

ADAMSON, WHO also directed the first two "Shrek" films, wasn't sure he wanted to return to Narnia, even though the first film was acclaimed by critics, embraced by families and has grossed more than $748 million worldwide. But he looked into the eyes of the then-10-year-old Georgie Henley and changed his mind.

Henley plays Lucy, the youngest of the four Pevensie children who enter Narnia's timeless world. When Adamson was directing Henley in the first film, she couldn't cry when he needed her to, after the lion Aslan's death. Henley had always wept watching "The Lion King," so Adamson cued its DVD up, but that didn't work, either. Running out of ideas, the director shared with Henley his doubt that he would direct the next film. The tears finally came.

Months later, with the first film completed, Henley sidled up to the New Zealand-born director. "When you said you weren't going to do the sequel, were you saying that just to make me cry or because you really didn't want to do the sequel?" she asked Adamson. "That made me want to do it," the director says. "When you look into those eyes, you can't say no."

If that was an easy enough decision, wrestling Lewis' succinct book into a movie was far more problematic. In Lewis' telling, some 12 months have passed since the four children left Narnia, but it's 1,300 years later in the lands where the White Witch once ruled.

In the intervening centuries, as a dwarf named Trumpkin relates to the children, the Narnians have been driven underground by the usurper Miraz and the Telmarines, descendants of pirates. Caspian, the son of the rightful (but slain by Miraz) King Caspian, has had to flee before he too is killed. With the Telmarines massing for battle, the Narnians need the eldest Pevensie boy, Peter, and Caspian, who have their own rivalry, to somehow save their race.

It sounds more exciting than it reads. Four consecutive chapters are told in flashback, and Caspian vanishes from the story for dozens of pages at a time. While the book may be a classic of children's literature, it doesn't scream movie.

Adamson and his collaborators steered the book's characters toward three concurrent story lines: Caspian's flight and ascension, the children's discoveries and maturation, and Miraz's implicitly genocidal campaign against the Narnians and their rightful king.

At the same time, Adamson says, "I was trying to find the emotional reality" of the movie. If the first "Chronicles of Narnia" was a fable of faith and sacrifice, the second became a parable of loss -- how the passage from childhood to adulthood inevitably means that as you take on something new, you must abandon something else: Innocence is replaced by doubt, trust by suspicion, comfort by insecurity. It's an idea shaped in part by Adamson's experiences in Papau, New Guinea, where he lived as a child. He could never bring himself to revisit it as an adult, he says, "because the place that I grew up in had completely changed and I couldn't confront that loss. . . . But you don't want to create a movie that's a bummer, and our first draft was pretty cynical."

That cynicism has been replaced by mounting (and sometimes made-up) conflict; it's clear from "Prince Caspian's" first frenetic frames the book is more guide than bible. Lewis writes that when Caspian fled Miraz's castle, "All night he rode southward . . .," and that's about as nail-biting as it gets. In Adamson's opening sequence, it's a pounding chase filled with peril. When Trumpkin (Peter Dinklage) later tells the children, "You may find Narnia a more savage place than you remember," he isn't kidding.

"I've really tried to stay true to the major themes of the book, the major events, and also have some invention," Adamson says back in his London postproduction suite, where eight assistant editors are frantically cutting in special effects shots (the first film had nine months in which to finish after photography wrapped, while "Prince Caspian" had about seven). Close readers of the book will notice that one of the movie's biggest departures is how quickly Caspian and Peter join forces.

The scale of the film also is noticeably grander. The opening sequence alone includes footage shot in the Czech Republic, Poland, New Zealand and Slovenia. "I think it's a much more beautiful movie," says Oren Aviv, Disney's production president, "just in terms of the scale and the scope of the locations." Even with unfinished effects, "Prince Caspian" tested better in a research screening than the first film.

SCORING UNDER THE GUN

WITH only a few weeks left to lock the movie, Adamson, in the Soho scoring stage, had asked composer Harry Gregson-Williams to move up a scoring cue by a few frames.

Adamson made the decision around 2 p.m., and by 4 p.m. at Abbey Road Studios (yes, that Abbey Road), Gregson-Williams already had made the change. Nervously chewing at the stubs of his fingernails, the composer in the next few days would assemble a 119-voice choral group. "I still have the whole battle scene to do," he says. If the film has approximately two hours of score, Gregson-Williams still had 30 minutes of music to finish.

Adamson isn't worried, though. The second movie may have been trickier at every turn, but it nevertheless was coming together. In Narnia, magical things happen.

john.horn@latimes.com

1 Comments:

the makers of Prince Caspian kept to the original story better than i would have expected... i had heard they were going to make it into a silly pure-action flick, but thankfully this was not so much the case

Post a Comment

<< Home